Structural vs. Excisional Rhinoplasty

Another fundamental issue confronting the prospective rhinoplasty patient is the choice of excisional versus structural (or incisional) rhinoplasty. Excisional rhinoplasty refers to incremental excision (or removal) of nasal cartilage in order to alter contour of the nostrils and nasal tip. For the forefathers of rhinoplasty, the removal of skeletal tissue was the only known means of altering nasal tip shape. Although cosmetic results were often crude and prone to progressive deformity, alternative techniques were lacking, and patients were typically grateful for a less obtrusive, if imperfect nose. However, today’s consumer seeks a more perfect non-surgical and natural-appearing rhinoplasty outcome. The unsightly and stereotypical look characteristic of an over-aggressive excisional rhinoplasty is no longer considered acceptable.

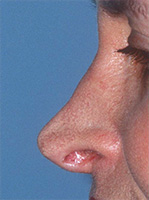

While the current trend in rhinoplasty surgery is a gradual shift toward cartilage preservation, many surgeons have been slow to recognize the dangers of excisional rhinoplasty. Surprisingly, aggressive cartilage excision is still widely practiced even today. As a result, stigmatic deformities, some of which may not fully manifest for months, years, or even decades following surgery, continue to affect a significant number of excisional rhinoplasty patients (Figure 1).

|

|

|

| FIGURE 1 A stereotypical post-op nasal tip deformity resulting from over-aggressive excisional rhinoplasty. Note the asymmetry, pinched tip and excessive nostril visibility. | ||

Usually, the stereotypical nasal deformity results from excessive removal of the lateral crus, the so-called "cephalic trim excision" (Figure 2). In this maneuver, the upper border of the lateral crus (a portion of the alar cartilage that supports the nostril) is removed, leaving a slender remnant of residual cartilage (Figure 2B). Ideally, just enough cartilage is removed to narrow the tip, but adequate cartilage is preserved to prevent nasal tip deformities. While this works in theory, in practice the threshold for nasal destabilization is nearly impossible to determine at the time of surgery. In fact, even well-meaning master surgeons may fail to preserve enough cartilage to avoid unwanted complications. As a result, the remnant cartilage can buckle from skin shrinkage; migrate upward from scar contracture, or a combination of both (Figure 2C-E). Furthermore, these alterations may be seen immediately or they may develop gradually as cartilage weakens with age. While some excisional procedures result in satisfactory outcomes, most experts agree that aggressive cartilage excision increases the risk of unsightly post-operative deformities. Although some surgeons still proudly boast a "complete" rhinoplasty in only 30 - 45 minutes using an excisional technique (and the closed approach), satisfactory long-term outcomes under these conditions are doubtful and the destructive impact of such practices are now being called into question.

|

|

|

|

|

| Natural alar cartilage. |

Missing cartilage after aggressive cephalic trim. | Buckling of cartilage. | Upward retraction of cartilage remnant (alar notching). | Upward retraction of tip unit (tip over-rotation or pig nose). |

| FIGURE 2 Potential tip deformities resulting from an aggressive cephalic trim maneuver. | ||||

Fortunately, there is now an effective alternative to excisional rhinoplasty. Although technically more demanding than cartilage excision, structural rhinoplasty emphasizes the importance of preserving skeletal support in order to avoid the complications of over-zealous cartilage removal. Rather than cutting, removing, and discarding large amounts of nasal cartilage (and potentially triggering a progressive and uncontrolled collapse of the weakened nasal framework), structural rhinoplasty relies upon repositioning and reshaping (e.g. folding) of tip cartilage to achieve a more attractive nasal contour. This simple yet effective concept maximizes skeletal integrity, which in turn dramatically improves the accuracy, reliability, and safety of cosmetic nasal surgery. Although some tissue excision is still unavoidable, such as with removal of a nasal bridge hump, a bulbous tip can now be dramatically transformed with little or no cartilage removal (Figure 3.).

|

|

|

|

| FIGURE 3 Before (left) and after (right) photographs of a structural rhinoplasty patient of Dr. Davis. Nearly 100% of the tip cartilage was preserved and multiple cartilage grafts were added to stabilize tip shape. | |

The resulting tip shape is elegant and natural, yet sturdy, with far less risk of airway collapse or delayed deformity. Furthermore, in patients with naturally weak nasal cartilage, cartilage grafts can be used to reinforce key structural elements and further protect the nose from delayed deformity. By combining the enhanced surgical exposure of open rhinoplasty with the principles of structural rhinoplasty, cartilage grafts can be positioned more precisely and then immobilized with suture fixation, further ensuring a strong and attractive nasal contour. When applied correctly, the grafts remain unseen and become permanently incorporated into the newly shaped nasal framework (Figure 3). Although a successful rhinoplasty still requires a skillful surgeon to artfully reconfigure a misshapen nose, the advent of structural rhinoplasty ensures that the attractive new nose will better withstand the inevitable rigors of wound-healing, disease, and aging. In addition, structural rhinoplasty also greatly reduces the risk of stereotypical nasal deformities such as pinching, nostril retraction, or overly prominent nostrils — the "operated look" characteristic of excessive alar cartilage excision. In fact, with structural rhinoplasty, what is not performed is just as important as what is. Hence the four R’s of structural rhinoplasty — Retain, Reposition, Reshape and Reinforce — have become the new gold standard for contemporary nasal surgery. It should also come as no surprise that most successful rhinoplasty surgeons employ structural rhinoplasty in one form or another.