Revision Rhinoplasty

The emotional impact of a failed rhinoplasty can be devastating. Rather than gaining a long-awaited nasal enhancement, the patient is left with a disappointing and unfamiliar facial appearance. The resulting impact upon self-esteem and self-confidence can vary, but for some, embarrassment, insecurity and depression can affect nearly every facet of daily life.

Although the causes of a failed rhinoplasty are many, including non-compliance on behalf of the patient, one of the most devastating causes is technical incompetence. Instead of a natural-appearing nose with an attractive contour, substandard surgery can produce an unnatural and awkward appearance that is decidedly less attractive than the original (birth) nose. In addition to the initial cosmetic deformity, surgical destabilization of the nasal tissues often results in further deformity via a slowly progressive distortion of the nasal skeleton, usually with a corresponding deterioration in nasal function. In addition to cosmetic and functional deficits, the victim of technical incompetence must also cope with anger, disappointment and regret, all while seeking a trustworthy surgeon to rebuild the damaged and misshapen nose.

Repairing Damage from a Prior Rhinoplasty

While restoring a surgically-damaged nose may appear deceptively simple, the medical and artistic challenge is considerable — typically far more complex than the initial rhinoplasty. Thin and delicate skeletal components of precise three-dimensional shape must be recreated to strengthen or replace shredded, collapsed, twisted (or even absent) skeletal remnants. Each fabricated component must possess mirror-image symmetry that mimics the opposing counterpart, and the finished structure must be vertically aligned to appear visually "straight". Seams and joints must be invisible, and the entire structure must be harmoniously proportioned to fit the surrounding face. While the outer contour must be smooth and attractive, the air passages must also remain large enough to facilitate comfortable nasal airflow. Once assembled, the entire skeletal framework must possess sufficient strength to withstand the long-term forces of distortion commonly exerted by healing skin and soft tissues. Although swelling must be minimized to reduce unwanted scar formation, blood flow must also be optimized to nourish surgically-traumatized tissues and enhance immune function. All of this must be accomplished quickly before swelling, bleeding and anesthetic effects distort and obscure the surgical field. For this reason, restoration of the failed rhinoplasty, commonly known as revision rhinoplasty, is widely regarded among the most challenging of all cosmetic endeavors.

Several important differences between primary (first-time) rhinoplasty and revision rhinoplasty are worth noting. First, revision rhinoplasty takes far more time. Because of the obstacles posed by scar tissue and the increase complexity of surgery, revision cases require at least 4-5 hours of total operative time. By the same token, the more difficult dissection, the greater length of surgery, and the presence of pre-existing tissue damage also equate to a much longer period of recovery. Patients with thin healthy skin may require 6-12 months, whereas patients with thick scar-prone skin may require up to two years for all manifestations of inflammation to resolve.

Use of Cartilage Graft Material in Rhinoplasty

In addition to increased treatment time, revision rhinoplasty nearly always requires the use of graft material. Graft material is living tissue, usually in the form of cartilage, which is harvested from the patient's own body and then used to replace missing or damaged skeletal tissues. Even patients seeking a smaller, more delicate nose may require cartilage grafting. Depending upon the extent of nasal tissue damage, the surgeon's preference, and the patient's willingness to authorize graft harvest, cartilage grafts may be obtained from one or more locations. Because the human body has only three sources of surplus cartilage and because each source yields cartilage of different shape, size, and consistency, the use of graft materials varies widely from patient to patient.

The following summary describes the advantages and disadvantages of each cartilage donor source:

Nasal Septum (Septal) Cartilage

The dividing wall that separates the right and left nasal passage is called the nasal septum. The septum is roughly the size of a credit card and is composed of septal cartilage in the front and skeletal bone deeper inside, while both sides are covered with mucous membranes. Although the outer perimeter of septal cartilage must be preserved to support the external nose; the remaining cartilage can be safely removed to obtain graft material for nasal reconstruction. See Figure 1

|

| FIGURE 1 Harvested septal cartilage. |

The process of septal graft harvest is very similar to a nasal septoplasty, in which deviated septal cartilage is removed to open blocked nasal passages. In either case, mucous membranes are preserved to prevent formation of a hole in the septum, a defect known as a septal perforation. However, unlike septoplasty in which the excised cartilage is destroyed, donor cartilage is removed as a single quarter-sized piece, strategically subdivided into replacement parts, and then re-implanted to replace damaged or weakened skeletal components.

Although the advantages of septal cartilage are many, the main drawback is the limited supply of available tissue. Unfortunately, patients with severe septal deviation, a history of previous septoplasty, or previously damaged septal cartilage, may not have sufficient surplus cartilage to rebuild a badly damaged nose. Nevertheless, a "virgin" septum often contains adequate donor tissue for most revision cases and can be harvested without the need for a separate surgical site. Moreover, septal cartilage is strong, yet thin and flexible, giving it physical characteristics that most closely resemble natural tip cartilage. In addition to being convenient to harvest, septal cartilage is also resistant to resorption, warping and infection; and in my opinion, septal cartilage is the single best material for rebuilding a damaged nose.

Ear (Conchal) Cartilage

The bowl-shaped portion of the external ear that lies just behind the ear canal is called the conchal bowl. When necessary, cartilage from the conchal bowl can be harvested through a small incision hidden in the post-auricular crease. In most individuals, a quarter-sized piece of ear cartilage can be removed without affecting the shape or appearance of the outer ear. See Figure 2

|

| FIGURE 2 Harvested ear cartilage. |

However, unlike septal cartilage which is flat, thin and flexible, ear cartilage is thick, curled and prone to cracking. Although ear cartilage is also resistant to infection, warping and resorption, its awkward shape, thickness and limited availability make it a less than ideal graft material. Obtaining ear cartilage also requires one or more additional surgical sites with modest associated discomfort. Nevertheless, in certain situations ear cartilage can be used effectively to enhance nasal contour.

Rib (Costal) Cartilage

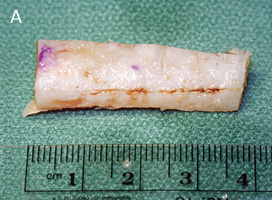

The human rib cage is composed mostly of bone, but in the area adjacent to the sternum (breast bone), ribs are made of cartilage. Although cartilage strength, shape, and thickness vary widely among individuals, segments of cartilage measuring 2-3 inches in length can be removed from the rib cage for use in nasal reconstruction. See Figure 3

|

|

| FIGURE 3 Harvested rib cartilage before (A) and after (B) carving. |

Unlike septal or conchal cartilage, rib cartilage is available in more than adequate amounts. However, removing rib cartilage is time consuming, painful, and potentially more dangerous. Although lung injury is extremely rare, a chest wall scar of 1-2 inches in length is necessary for adequate exposure and soreness may persist for days or weeks following surgery. And while rib cartilage is abundant, it is far from ideal. When thinned to create a natural-appearing nose, rib cartilage becomes weak and brittle, with a strong tendency to curl or warp in the days, weeks, and months following surgery. Thus, noses rebuilt from rib cartilage, by necessity, are sometimes large and bulky reflecting the need to avoid thin rib cartilage grafts. While this may be acceptable in certain circumstances, such as men who prefer strong noses, for those seeking a slender and delicate nasal contour, rib cartilage poses a significant risk of warping. However, for patients with severely damaged, over-resected noses, rib cartilage is often the only viable treatment option, particularly if septal and conchal cartilage has already been depleted.

Although warping can be minimized with optimal technique, delayed deformity is an ever-present risk in virtually any patient undergoing rib cartilage grafting. Rib cartilage is also more susceptible to infection and probably takes longer to fully re-vascularize relative to septal or ear cartilage. On the other hand, warping can often be treated effectively with additional surgery, and if given sufficient time and resources, an experienced surgeon can restore most devastated noses using rib cartilage. Hence, although generally regarded as the treatment of last resort, rib cartilage is nevertheless an indispensable component of the rhinoplasty tool chest.

Synthetic Tissue Substitutes

In the severely over-resected nose, large amounts of cartilage are needed to augment the flattened and under-projected nasal bridge. Owing to the relative scarcity of septal or conchal cartilage and the risk of warping associated with rib cartilage, reconstruction of the nasal bridge is sometimes best accomplished using synthetic implant material. Like rib cartilage, modern synthetic implants offer a virtually endless supply of augmentation material, only without the pain, scar, and risk associated with rib harvest. Newer pre-shaped porous implant materials like Medpor® are virtually immune to resorption or warping and can be precision carved for a custom fit. Although potentially susceptible to infection or rejection, these materials have an outstanding clinical track record when placed in healthy recipient tissues and should provide a lifetime of normal service. While I avoid the use of synthetic materials in the nasal tip or in infection-prone noses such as cocaine abusers where complication rates are considerably higher, my experience with Medpor® in nasal bridge augmentation has been very favorable and I continue to offer it as a reasonable alternative to rib cartilage.

Combined Cartilage Grafts

In severely damaged noses, the best surgical results are sometimes achieved with a variety of reconstructive materials. The combined use of septal, conchal, and/or rib cartilage grafts, with or without synthetic materials, enhances the surgical outcome by employing tissues with a range of individual characteristics. Since the precise skeletal deformity is unknown prior to surgery, the final choice of reconstructive materials is best reserved for the operating room, and patients willing to authorize the full scope of reconstructive materials stand a much better chance of achieving the desired surgical outcome. While this adds complexity, time and cost to the surgical reconstruction, the benefits of a properly restored nose tend to justify the additional expenditures.

Soft Tissue Damage and Response

Another distinguishing characteristic of revision rhinoplasty is the inevitable presence of soft tissue damage resulting from previous nasal surgery. Soft tissues overlying the nasal skeleton, such as skin, muscle, fascia and fat are unavoidably injured during any rhinoplasty. But unlike virgin soft tissues which tend to tolerate surgical disruption with minimal inflammation, swelling or scar formation, previously operated tissues exhibit inflammatory responses that are typically more severe and which may potentially compromise the cosmetic outcome. These adverse tissue responses also become increasingly more prevalent each time the nose is surgically disrupted, making revision surgery far more challenging in the patient with a history of multiple previous rhinoplasty procedures. In fact, the limiting factor in revision rhinoplasty is often the soft tissue response, since a well-constructed skeletal framework may be ruined by adverse inflammatory reactions.

In some cases, waiting 12-18 months (or longer) for all of the surgical inflammation to fully resolve may help to diminish the adverse affects of subsequent surgery, but coping with the emotional effects of a failed rhinoplasty for that length of time can be burdensome for the patient. A wise surgeon will also seek to avoid adverse tissue responses with delicate, tissue-friendly surgical technique and good blood pressure control, and by restricting patients from activities that promote inflammation. However, in some patients, the genetically pre-determined inflammatory responses and the cumulative degree of soft tissue damage are just too severe as to permit a successful revision rhinoplasty. Moreover, there is no conclusive means of identifying these patients prior to surgery, making revision rhinoplasty a gamble for every prospective patient. On the other hand, most prospective patients are favorable candidates for a successful revision surgery. In fact, for some patients, the odds of a successful cosmetic outcome are comparable to a straight-forward primary rhinoplasty.

In every revision case, a thorough pre-operative assessment of the medical history, nasal architecture, and nasal tissue characteristics is necessary to realistically define the odds of a successful surgical restoration. Surgeons who ignore or misread the warning signs of stubborn or damaged tissues risk further harm with additional surgery.

The following soft tissue characteristics are major determinants in the prognosis for any revision rhinoplasty:

Blood Supply

Rebuilding a damaged outer nose has similarities to rebuilding an A-frame house. Both structures have an architectural framework that provides structural support and determines the overall, length, width and shape of the structure. In order to modify the structure's shape, the framework must be exposed and then physically reconfigured. In the nose, the structural framework is the nasal skeleton, consisting of cartilage and bone, whereas the house is typically wood and concrete. However, unlike a house, the nasal framework is composed entirely of living tissue – tissues that must have a constant flow of blood to remain viable. In the nose, nutrients such as oxygen, glucose, minerals, etc, are delivered to the skeletal framework through a network of tiny blood vessels found within the overlying skin and underlying mucous membranes. By necessity, any type of nasal surgery (or nasal injury) causes varying degrees of damage to this circulatory network. While the human body has an incredible capacity to heal from such damage, recovery is never fully complete and some blood vessels are permanently lost.

Fortunately, the nasal circulation has excess capacity, so the overall circulatory impact of a well-executed surgical intervention is usually negligible. However, repeated surgeries, especially when combined with poor surgical technique, can eventually impair circulatory function. Moreover, the surgery itself causes additional temporary circulatory impairment as a consequence of swelling and inflammation. When the total circulatory impairment exceeds the threshold for minimal tissue perfusion, tissues become oxygen-deprived, or ischemic, and complications such as cell death, infection and tissue resorption soon develop.

Because revision rhinoplasty relies almost entirely upon the transplantation of cartilage into the nose, a healthy recipient blood supply is a key element in ensuring survival of grafted tissues. A robust circulation not only ensures prompt re-vascularization of the transplanted cartilage grafts, it also lowers the risk of infection and graft resorption. Gentle surgical technique, avoidance of tobacco or nicotine, and good supportive care can help to optimize circulatory support to the vulnerable grafted tissues.

However, in noses with severely damaged circulation, such as those subjected to multiple previous rhinoplasty procedures, the likelihood of graft resorption, infection, and even skin necrosis (death) are increased, especially when coupled with smoking, infection, cocaine abuse, excessive swelling, diabetes or other conditions, medications or supplements that impair circulation. In this patient population, good surgical technique is often negated by poor circulation and the results of surgery are usually disappointing.

Skin Elasticity

Another physical characteristic affecting revision rhinoplasty is elasticity of the skin and the underlying soft tissues. Because revision rhinoplasty often involves rebuilding noses after excessive tissue removal (the so-called over-resected nose), increases in nasal length, tip projection, and bridge height are frequent cosmetic objectives. In order to accommodate enlargement of the nasal framework, the overlying soft tissues must stretch easily without undue tension. However, naturally thick leathery skin with poor elasticity, or inelastic skin scarred from multiple previous surgeries, both resist stretching and may bend, shift, or collapse the newly rebuilt nasal framework. In severe cases, excessive skin tension can even compromise blood flow leading to the additional risks described above. Patients with soft elastic skin are generally much better candidates for revision rhinoplasty all other factors being equal.

Scar Tissue (Fibrosis) Formation

Soon after the soft tissue blanket is surgically lifted to permit cosmetic modification of the nasal framework, scar tissue (or fibrosis) begins to develop. Special cells called fibroblasts deposit collagen and other substances to "glue" tissue layers back together and restore structural integrity to the nose. Without this miraculous healing response, surgery would be all but impossible. However, the extent of scar accumulation varies widely among individuals and the body's complex mechanism for controlling scar formation is poorly understood. Although the extent of scar accumulation is known to be genetically pre-determined, various external factors can also increase or decrease the amount of subcutaneous scar formation. While some scar formation is essential, excessive scarring results in overly thick and leathery skin which adversely affects nasal appearance.

Because severe swelling (or edema) after nasal surgery increases the risk of scar formation, supportive efforts are directed at minimizing or avoiding those external factors that contribute to prolonged swelling. For most patients, these restrictions are tedious and annoying, but are ultimately worthwhile as they often result in a far more favorable cosmetic outcome. Minimizing blood surges to the nose from blood pressure elevations avoids vascular congestion and trapping of additional fluids within the injured tissues. Patients are advised to keep the nose elevated high above the heart, to avoid elevations in heart rate from exercise or exertion, and to prevent further skin injury from sunburn or harsh skin products such as exfoliants, acne scrubs, etc. For those patients with stubborn swelling that persists despite all reasonable preventative measures, additional treatment options such as compressive taping, nasal steroid sprays, or steroid (Kenalog) injections may be necessary to prevent permanent subcutaneous scarring.

Patients with naturally thick sebaceous skin, acne, or a previous history of hypertrophic scar/keloid formation are at greatest risk for unwanted scarring, but even patients with a smooth, delicate complexion are at risk for scar contracture. Unlike fibrosis, scar contracture results from myofibroblasts, small cells that cause the overlying skin to tighten and shrink. As with fibrosis, some contracture is desirable since tightly adherent skin has a more pleasing surface definition. However, excessive scar contracture, known as the "shrink-wrap" phenomenon, can bend, buckle, shift or distort the underlying cartilage framework and cause contour imperfections. Thus, scar formation potentially affects skin of every type and scarring tendencies are increased in all revision surgery patients.

Patience and Conservatism in Revision Rhinoplasty

Taken as a whole, revision rhinoplasty is a complex undertaking with numerous potential risks and pitfalls. Obtaining suitable cartilage, assembling the cartilage in a stable and attractive configuration, and managing the soft tissues to promote a favorable and complication-free recovery is a difficult challenge that even some accomplished rhinoplasty surgeons choose to avoid.

While nearly all revision rhinoplasty patients can be improved when sound surgical principles are properly applied, absolute perfection is virtually impossible. Patients must also understand that modern medicine cannot cure all ailments and that the severely devastated nose cannot always be restored in a single operation. Due to pre-existing tissue damage and the limitations outlined above, cosmetic gains are often hard-fought and incomplete, making step-wise improvement a necessity in the severely injured nose. However, some of my most dramatic outcomes have resulted from staged reconstructions in which tissues were allowed to heal fully and completely between operations. While this approach has obvious economic and emotional downsides, the results obtained would be impossible using a single-surgery approach. Moreover, attempting to restore a devastated nose to perfection in a single operation may result in catastrophic failure from over-stressing already tenuous tissues.

Clinical experience, derived from thousands of nasal surgeries, has taught me the value of patience and conservatism in revision rhinoplasty, and patients who seek quick fixes or unrealistic outcomes are likely to dig deeper and deeper holes for themselves, from which they may never emerge. While an accomplished surgeon will seek to achieve the best possible outcome in any patient, the desire to achieve a dramatic result must be balanced against the risks and potential complications inherent in revision rhinoplasty. Knowing when to back off is the true sign of a master surgeon, and the Hippocratic Oath of "do no harm" was never more applicable.